plunderphonics

source http://www.plunderphonics.com/xhtml/xplunder.html

—–

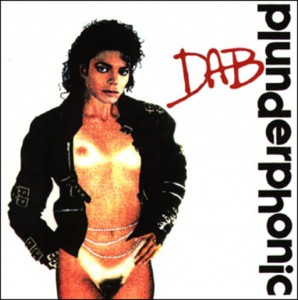

“Plunderphonics, or Audio Piracy as a Compositional Prerogative”

– as presented by John Oswald to the Wired Society Electro-Acoustic Conference in Toronto in 1985.

Musical instruments produce sounds. Composers produce music. Musical instruments reproduce music. Tape recorders, radios, disc players, etc., reproduce sound. A device such as a wind-up music box produces sound and reproduces music. A phonograph in the hands of a hip hop/scratch artist who plays a record like an electronic washboard with a phonographic needle as a plectrum, produces sounds which are unique and not reproduced – the record player becomes a musical instrument. A sampler, in essence a recording, transforming instrument, is simultaneously a documenting device and a creative device, in effect reducing a distinction manifested by copyright.

Free samples

These new-fangled, much-talked-about digital sound sampling devices, are, we are told, music mimics par excellence, able to render the whole orchestral panoply, plus all that grunts, or squeaks. The noun “sample” is, in our comodified culture, often pre-fixed by the adjective free, and if one is to consider predicating this subject, perhaps some thinking aloud on what is not allowable auditory appropriation is to be heard.

Some of you, current and potential samplerists, are perhaps curious about the extent to which you can legally borrow from the ingredients of other people’s sonic manifestations. Is a musical property properly private, and if so, when and how does one trespass upon it? Like myself, you may covet something similar to a particular chord played and recorded singularly well by the strings of the estimable Eastman Rochester Orchestra on a long-deleted Mercury Living Presence LP of Charles Ives’ Symphony #3, itself rampant in unauthorized procurements. Or imagine how invigorating a few retrograde Pygmy (no slur on primitivism intended) chants would sound in the quasi-funk section of your emulator concerto. Or perhaps you would simply like to transfer an octave of hiccups from the stock sound library disk of a Mirage to the spring-loaded tape catapults of your Melotron.

Can the sounding materials that inspire composition be sometimes considered compositions themselves? Is the piano the musical creation of Bartolommeo Cristofori (1655-1731) or merely the vehicle engineered by him for Ludwig Van and others to manoeuver through their musical territory? Some memorable compositions were created specifically for the digital recorder of that era, the music box. Are the preset sounds in today’s sequencers and synthesizers free samples, or the musical property of the manufacturer? Is a timbre any less definably possessable than a melody? A composer who claims divine inspiration is perhaps exempt from responsibility to this inventory of the layers of authorship. But what about the unblessed rest of us?

Let’s see what the powers that be have to say. ‘Author’ is copyrightspeak for any creative progenitor, no matter if they program software or compose hardcore. To wit: “An author is entitled to claim authorship and to preserve the integrity of the work by restraining any distortion, mutilation or other modification that is prejudicial to the author’s honor or reputation.” That’s called the ‘right of integrity’ and it’s from the Canada Copyright Act. A recently published report on the proposed revision of the Act uses the metaphor of land owners’ rights, where unauthorized use is synonymous with trespassing. The territory is limited. Only recently have sound recordings been considered a part of this real estate.

Blank tape is derivative, nothing of itself

Way back in 1976, ninety nine years after Edison went into the record business, the U.S. Copyright Act was revised to protect sound recordings in that country for the first time. Before this, only written music was considered eligible for protection. Forms of music that were not intelligible to the human eye were deemed ineligible. The traditional attitude was that recordings were not artistic creations, “but mere uses or applications of creative works in the form of physical objects.”

Some music oriented organizations still retain this ‘view’. The current Canadian Act came into being in 1924, an electric eon later than the original U.S. Act of l909, and up here “copyright does subsist in records, perforated rolls and other contrivances by means of which sounds may be mechanically reproduced.”

Of course the capabilities of mechanical contrivances are now more diverse than anyone back at the turn of the century forecasted, but now the real headache for the writers of copyright is the new electronic contrivances, including digital samplers of sound and their accountant cousins, computers. Among “the intimate cultural secretions of electronic, biological, and written communicative media” the electronic brain business is cultivating, by grace of its relative youth, pioneering creativity and a corresponding conniving ingenuity. The popular intrigue of computer theft has inspired cinematic and paperback thrillers while the robbery of music is restricted to elementary poaching and blundering innocence. The plots are trivial: Disney accuses Sony of conspiring with consumers to make unauthorized mice. Former Beatle George Harrison is found guilty of an indiscretion in choosing a vaguely familiar sequence of pitches.

The dubbing-in-the-privacy-of-your-own-home controversy is actually the tip of a hot iceberg of rudimentary creativity. After decades of being the passive recipients of music in packages, listeners now have the means to assemble their own choices, to separate pleasures from the filler. They are dubbing a variety of sounds from around the world, or at least from the breadth of their record collections, making compilations of a diversity unavailable from the music industry, with its circumscribed stables of artists, and an ever more pervasive policy of only supplying the common denominator.

The Chiffons/Harrison case, and the general accountability of melodic originality, indicates a continuing concern for what amounts to the equivalent of a squabble over the patents to the Edison cylinder.

The Commerce of Noise

The precarious commodity in music today is no longer the tune. A fan can recognize a hit from a ten millisecond burst, faster than a Fairlight can whistle Dixie. Notes with their rhythm and pitch values are trivial components in the corporate harmonization of cacophony. Few pop musicians can read music with any facility. The Art of Noise, a studio based, mass market targeted recording firm, strings atonal arrays of timbres on the line of an ubiquitous beat. The Emulator fills the bill. Singers with original material aren’t studying Bruce Springsteen’s melodic contours, they’re trying to sound just like him. And sonic impersonation is quite legal. While performing rights organizations continue to farm for proceeds for tunesters and poetricians, those who are shaping the way the buck says the music should be, rhythmatists, timbralists and mixologists under various monikers, have rarely been given compositional credit.

At what some would like to consider the opposite end of the field, among academics and the salaried technicians of the orchestral swarms, an orderly display of fermatas and hemidemisemiquavers on a page is still often thought indispensible to a definition of music, even though some earnest composers rarely if ever peck these things out anymore. Of course, if appearances are necessary, a computer program and printer can do it for them.

Musical language has an extensive repertoire of punctuation devices but nothing equivalent to literature’s ” ” quotation marks. Jazz musicians do not wiggle two fingers of each hand in the air, as lecturers often do, when cross referencing during their extemporizations, because on most instruments this would present some technical difficulties – plummeting trumpets and such.

Without a quotation system, well-intended correspondences cannot be distinguished from plagiarism and fraud. But anyway, the quoting of notes is but a small and insignificant portion of common appropriation.

Am I underestimating the value of melody writing? Well, I expect that before long we’ll have marketable expert tune writing software which will be able to generate the banalities of catchy permutations of the diatonic scale in endless arrays of tuneable tunes, from which a not necessarily affluent songwriter can choose; with perhaps a built-in checking lexicon of used-up tunes which would advise Beatle George not to make the same blunder again.

Chimeras of sound

Some composers have long considered the tape recorder a musical instrument capable of more than the faithful hi-fi transcriber role to which manufacturers have traditionally limted its function. Now there are hybrids of the electronic offspring of acoustic instruments and audio mimicry by the digital clones of tape recorders. Audio mimicry by digital means is nothing new; mechanical manticores from the 19th century with names like the Violano-virtuoso and the Orchestrion are quaintly similar to the Synclavier Digital Music System and the Fairlight CMI (computer music instrument). In the case of the Synclavier, what is touted as a combination multi-track recording studio and simulated symphony orchestra looks like a piano with a built-in accordian chordboard and LED clock radio.

The composer who plucks a blade of grass and with cupped hands to pursed lips creates a vibrating soniferous membrane and resonator, although susceptible to comments on the order of “it’s been done before”, is in the potential position of bypassing previous technological achievement and communing directly with nature. Of music from tools, even the iconoclastic implements of a Harry Partch or a Hugh LeCaine are susceptible to the convention of distinction between instrument and composition. Sounding utensils, from the erh-hu to the Emulator, have traditionally provided such a potential for varied expression that they have not in themselves been considered musical manifestations. This is contrary to the great popularity of generic instrumental music (“The Many Moods of 101 Strings”, “Piano for Lovers”, “The Truckers DX-7” etc.), not to mention instruments which play themselves, the most pervasive example in recent years being pre-programmed rhythm boxes. Such devices, as are found in lounge acts and organ consoles, are direct kin to the juke box: push a button and out comes music. J.S.Bach pointed out that with any instrument “all one has to do is hit the right notes at the right time and the thing plays itself.” The distinction between sound producers and sound reproducers is easily blurred, and has been a conceivable area of musical pursuit at least since John Cage’s use of radios in the Forties.

Starting from scratch

Just as sound producing and sound reproducing technology becomes more interactive, listeners are once again, if not invited, nonetheless encroaching upon creative territory. This prerogative has been largely forgotten in recent decades. The now primitive record-playing generation was a passive lot (indigenous active form scratch belongs to the post-disc, blaster/walkman era). Gone were the days of lively renditions on the parlor piano.

Computers can take the expertise out of amateur music making. A current music-minus-one program retards tempos and searches for the most ubiquitous chords to support the wanderings of a novice player. Some audio equipment geared for the consumer inadvertently offers interactive possibilities. But manufacturers have discouraged compatability between their amateur and pro equipment. Passivity is still the dominant demographic. Thus the atrophied microphone inputs which have now all but disappeared from premium stereo cassette decks.

As a listener my own preference is the option to experiment. My listening system has a mixer instead of a receiver, an infinitely variable speed turntable, filters, reverse capability, and a pair of ears.

An active listener might speed up a piece of music in order to perceive more clearly its macrostructure, or slow it down to hear articulation and detail more precisely. Portions of pieces are juxtaposed for comparison or played simultaneously, tracing “the motifs of the Indian raga Darbar over Senegalese drumming recording in Paris and a background mosaic of frozen moments from an exotic Hollywood orchestration of the 1950’s (a sonic texture like a “Mona Lisa” which in close-up, reveals itself to be made up of tiny reproductions of the Taj Mahal.”

During World War II concurrent with Cage’s re-establishing the percussive status of the piano, Trinidadians were discovering that discarded oil barrels could be cheap, available alternatives to their traditional percussion instruments which were, because of the socially invigorating potential, banned. The steel drum eventually became a national asset. Meanwhile, back in the States, for perhaps similar reasons, scratch and dub have, in the Eighties, percolated through the black American ghettos. Within an environmentally imposed, limited repertoire of possessions a portable disco may have a folk music potential exceeding that of the guitar. Pawned and ripped-off electronics are usually not accompanied by user’s guides with consumer warnings such as “this blaster is a passive reproducer”. Any performance potential found in an appliance is often exploited. A record can be played like an electronic washboard. Radio and disco jockeys layer the sounds of several recordings simultaneously. The sound of music conveyed with a new authority over the airwaves is dubbed, embellished and manipulated in kind.

The medium is magnetic

Piracy or plagiarism of a work occur, according to Milton, “if it is not bettered by the borrower”. Stravinsky added the right of possession to Milton’s distinction when he said,. “A good composer does not imitate; he steals.” An example of this better borrowing is Jim Tenney’s “Collage 1” (l961) in which Elvis Presley’s hit record “Blue Suede Shoes” (itself borrowed from Carl Perkins) is transformed by means of multi-speed tape recorders and razorblade. In the same way that Pierre Schaeffer found musical potential in his object sonore, which could be, for instance, a footstep, heavy with associations, Tenney took an everyday music and allowed us to hear it differently. At the same time, all that was inherently Elvis radically influenced our perception of Jim’s piece.

Fair use and fair dealing are respectively the American and the Canadian terms for instances in which appropriation without permission might be considered legal. Quoting extracts of music for pedagogical, illustrative and critical purposes have been upheld as legal fair use. So has borrowing for the purpose of parody. Fair dealing assumes use which does not interfere with the economic viability of the initial work.

In addition to economic rights, moral rights exist in copyright, and in Canada these are receiving a greater emphasis in the current recommendations for revision. An artist can claim certain moral rights to a work. Elvis’ estate can claim the same rights, including the right to privacy, and the right to protection of “the special significance of sounds peculiar to a particular artist, the uniqueness of which might be harmed by inferior unauthorized recordings which might tend to confuse the public about an artist’s abilities.

At present, in Canada, a work can serve as a matrix for independent derivations. Section 17(2)(b) of the Copyright Act of Canada provides “that an artist who does not retain the copyright in a work may use certain materials used to produce that work to produce a subsequent work, without infringing copyright in the earlier work, if the subsequent work taken as a whole does not repeat the main design of the previous work.”

My observation is that Tenney’s “Blue Suede” fulfills Milton’s stipulation; is supported by Stravinsky’s aphorism; and does not contravene Elvis’ morality or Section 17(2)(b) of the Copyright Act.

Aural wilderness

The reuse of existing recorded materials is not restricted to the street and the esoteric. The single guitar chord occuring infrequently on H. Hancock’s hit arrangement “Rocket” was not struck by an in-studio union guitarist but was sampled directly from an old Led Zepplin record. Similarly, Michael Jackson unwittingly turns up on Hancock’s follow-up clone “Hard Rock”. Now that keyboardists are getting instruments with the button for this appropriation built in, they’re going to push it, easier than reconstructing the ideal sound from oscillation one. These players are used to fingertip replication, as in the case of the organ that had the titles of the songs from which the timbres were derived printed on the stops.

So the equipment is available, and everybody’s doing it, blatantly or otherwise. Melodic invention is nothing to lose sleep over (look what sleep did for Tartini). There’s a certain amount of legal leeway for imitation. Now can we, like Charles Ives, borrow merrily and blatantly from all the music in the air?

Ives composed in an era in which much of music existed in a public domain. Public domain is now legally defined, although it maintains a distance from the present which varies from country to country. In order to follow Ives’ model we would be restricted to using the same oldies which in his time were current. Nonetheless, music in the public domain can become very popular, perhaps in part because the composer is no longer entitled to exclusivity, or royalty payments‹ a hit available for a song . Or as This Business of Music puts it, “The public domain is like a vast national park without a guard to stop wanton looting, without a guide for the lost traveller, and in fact, without clearly defined roads or even borders to stop the helpless visitor from being sued for trespass by private abutting owners.”

Professional developers of the musical landscape know and lobby for the loopholes in copyright. On the other hand, many artistic endeavours would benefit creatively from a state of music without fences, but where, as in scholarship, acknowledgement is insisted upon.

The buzzing of a titanic bumblebee

The property metaphor used to illustrate an artist’s rights is difficult to pursue through publication and mass dissemination. The hit parade promenades the aural floats of pop on public display, and as curious tourists should we not be able to take our own snapshots through the crowd (“tiny reproductions of the Taj Mahal”) rather than be restricted to the official souvenir postcards and programmes?

All popular music (and all folk music, by definition), essentially, if not legally, exists in a public domain. Listening to pop music isn’t a matter of choice. Asked for or not, we’re bombarded by it. In its most insidious state, filtered to an incessant bass-line, it seeps through apartment walls and out of the heads of walk people. Although people in general are making more noise than ever before, fewer people are making more of the total noise; specifically, in music, those with megawatt PA’s, triple platinum sales, and heavy rotation. Difficult to ignore, pointlessly redundant to imitate, how does one not become a passive recipient?

Proposing their game plan to apprehend the Titanic once it had been located at the bottom of the Atlantic, oceanographer Bob Ballard of the Deep Emergence Laboratory suggested “you pound the hell out of it with every imaging system you have.”

~ John Oswald, 1985

This paper was initially presented by Oswald at the Wired Society Electro-Acoustic Conference in Toronto in 1985. It was published in Musicworks #34, as a booklet by Recommended Quarterly and subsequently revised for the Whole Earth Review #57 as ‘Bettered by the borrower’.

— end of phile —

links:

http://www.plunderphonics.com/

pfony — http://pfony.com/

download Plunderphonics (John Oswald LP in mp3 format .rar archive) — http://www.autistici.org/2000-maniax/music/plunderphonics/

Plunderphonics (John Oswald LP) — http://isohunt.com/torrent_details/318934857/?tab=summary

Grayfolded (The Grateful Dead double CD) — http://isohunt.com/torrent_details/311393489/?tab=summary