I seguenti video mostrano il funzionamento di alcune macchine per il pressaggio dei dischi in vinile.

Filmed at Disco-Press, Belgium. September 25 2002

Fabricação de discos de vinil na Polysom, a última e única do Brasil, em Belford Roxo.

This promotional short for Irving Mills’ short-lived Master

and Variety labels not only gives us a glimpse of Ellington and his

band in the actual Master/Variety studios (as opposed to a soundstage

set), but is one of the very few film accounts of how records were

recorded, plated and pressed in the long-ago age of analog, shellac and

78 rpm. Narration is provided by pioneer radio announcer Alois Havrilla.

Video for Dutch artist Floris, shot on location in Europe’s biggest vinyl factory in Haarlem.

Noise music

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Noise( music ) is music composed of non-traditional musical elements, and lacks the structure associated with Western Music. A noise musician may incorporate, for example; manipulated recordings, static, feedback, live machine sounds, circuit bent instruments, non-musical vocal elements, or anything that makes a sound, etc.

Practitioners themselves do not generally refer to it as "Noise Music"; they just call it "Noise", tacking the term "music" on the end is generally only done when talking to those unfamiliar with the genre

[edit] History

[edit] Luigi Russolo

Luigi Russolo, a Futurist painter of the very early 20th century, was perhaps the first Noise artist. His 1913 manifesto L’Arte de Rumori, translated as The Art of Noises,

stated that the industrial revolution had given modern men a greater

capacity to appreciate more complex sounds. Russolo found traditional

melodic music confining and envisioned noise music as its future

replacement. He designed and constructed a number of noise-generating

devices called Intonarumori and assembled a noise orchestra to perform with them. A performance of his Gran Concerto Futuristico

(1917) was met with strong disapproval and violence from the audience,

as Russolo himself had predicted. None of his intoning devices have

survived, though recently some have been reconstructed and used in

performances. Although Russolo’s works bear little resemblance to

modern noise music, his pioneering creations cannot be overlooked as an

essential stage in the evolution of this genre, and many artists are

now familiar with his manifesto.

Other early composers

Composer Arnold Schoenberg‘s proclaimed "Emancipation of the dissonance"

(the idea that music could just as well be based upon dissonance as

consonance) in the early 20th century was probably the origin of noise

music. By the 1920s, composers (in particular Edgard Varèse and George Antheil)

began to use early mechanical musical instruments–such as the player

piano and the siren–to create music that referenced the noise of the

modern world. In the 1930s, under the influence of Henry Cowell in San Francisco, Lou Harrison and John Cage

began composing music for "junk" percussion ensembles — scouring

junkyards and Chinatown antique shops for appropriately tuned brake

drums, flower pots, gongs, and more. Cage started his Imaginary Landscape series in 1939, which combined elements like recorded sound, percussion, and (in the case of Imaginary Landscape #4) twelve radios. After the second world war, other composers (including G.M. Koenig, Iannis Xenakis, and Karlheinz Stockhausen) started to experiment with sound synthesis, tape machines and radio equipment to produce electronic music, often with very noisy sounds. Much of this music has proven influential on the creators of noise music.

With the advent of the radio, Pierre Schaeffer coined the term musique concrete

to refer to the peculiar nature of sounds on tape, separated from the

source that generated them initially. His ideas about non-referential

sounds take their most extreme form in noise music, which often blurs

or obscures the actions which produced the sounds while also suggesting

the physicality of sound itself.

The sudden affordability of home recording technology in the 1970s with the simultaneous influence of punk rock

established a new aesthetic and instigated what is commonly referred to

as noise music today. When anyone could produce noise, and anyone could

record and distribute it, then noise music provided a way for any

person (artist or non-artist) to experiment with sound as a painter

might with visual material.

[edit] Boyd Rice

American archivist and writer Boyd Rice has been a seminal influence on Noise music. Starting in 1975, Rice began experimenting with the possibilities of pure sound. In his live performances, he attached an electric fan to an electric guitar and also used an electric shoe polisher

as an instrument. He created extremely loud, cascading walls of noise

and played pieces of recorded conversations, news reports, and music

just beneath the threshold of comprehensibility. Rice has created works

that combine brutal soundscapes with various poetics. He has also

structured noise elements into harmonious, rhythmic pieces that defy

easy categorization.

[edit] Japan

Originally influenced by the sounds of European bands like Whitehouse and the Italian non-musician Maurizio Bianchi/M.

B., Japanese noise artists pushed this approach to an extreme of

loudness and density, which in turn became a major influence on western

noise bands. Sometimes known as "Japanoise"

(a pun not just in English, but even in Japanese: ジャパノイズ ), it is

usually associated with "harsh" characteristics including walls of white noise, non-linear pulses, arrhythmic beats, distorted sound loops, unintelligible dialogue, and sirens.

Since the late 1980s this Japanese style has been probably the most

prolific and noticeable part of the Noise Music scene. Likewise the

popularity and prolific output of musicians such as the aforementioned

Noise Music figurehead/posterboy Merzbow, C.C.C.C. and other names like KK Null, Masonna, The Gerogerigegege and Hanatarash (founded by Boredoms frontman, Yamatsuka Eye)

have made Japan something of a Mecca for many noise fans. In terms of

sales, Noise music is not particularly more popular in Japan than in

Europe or America. However, there is perhaps a higher level of

recognition from crossover with mainstream genres and events, such as

fashion shows or dance performances with music by noise artists, and a

comparatively large number of live noise performances are held in Tokyo.

Recently the noise scene has given birth to a form of freely improvised electronic music known by the press as onkyo-kei, with leading lights including the aforementioned Sachiko M.

[edit] Albums and non-noise influences

Lou Reed‘s double-LP album Metal Machine Music released in 1975 is an early, well-known example of noise music.

It is very likely that Reed was aware of the electronic drone music produced in the mid-60s by his Velvet Underground cohort John Cale with artists such as Tony Conrad and LaMonte Young (see the CD release of Inside the Dream Syndicate Volume 1: Day of Niagara).

In 1988, RRRecords released a series of anti-records in which ordinary vinyl LPs and, in some cases, flexidiscs were physically transformed into noise records.

[edit] Mixing of forms

In Canada, the Nihilist Spasm Band has been performing acoustic-based noise music since 1965. The aptly named noise rock fuses rock

to noise, usually with recognisable "rock" instrumentation, but with

greater use of distortion and electronic effects, varying degrees of

atonalism, improvisation and white noise. One of the best-known bands of this genre is Boredoms. This style is more like a "traditional" band compared to abstract or electronic noise and sometimes bears a similarity to grindcore. The name noisecore is also used to refer to noise-influenced hardcore techno or rock.

Fans of the genre sometimes distinguish between "harsh noise", the more well-known super-dense and abrasive sounds of Merzbow, Masonna

and similar artists, and other loose sub-genres like "rhythmic noise",

"power electronics", "free noise" and so on. Confusingly, some

industrial techno sub-genres have very similar names, i.e. power noise. Power noise is comparatively conventionally musical, and is not to be confused with power electronics, the synthesizer based subgenre of abstract and experimental noise performed by Whitehouse.

Free noise came equally out of the free jazz traditions, or at least

its outer boundaries such as Albert Ayler and John Zorn, as its harsh

noise influences and closely aligns itself with similar methods of

long, interactive improvisations between players; examples include Borbetomagus and WRONG.

One possible influence of noise music has been to change the way of

thinking about what is "musical" or "unmusical" noise, and recently

many different genres, such as techno and hip-hop, include some kinds

of sounds that could be viewed as "noise".

[edit] Methods and Inspirations

In much the same way the early modernists were inspired by primitive

art, some contemporary noisicians are excited by the archaic audio

technologies, such as wire-recorders, the 8-track cartridge, and vinyl

records. For instance, some still choose to release their work on

vinyl. Many artists not only build their own noise-generating devices,

but even their own specialized recording equipment[citation needed].

Many performances by noise artists are extremely loud and can be

near-deafening. The frequencies used by many are both shrieking and

overpowering.

David Jackman

said his first noise performance, albeit unintentional, was when he was

14 years old. He and his father demolished an old piano using an axe

and hammer. Jackman called it "a huge racket".[citation needed]

An outburst of emotion is the effect given by the performances of the group C.C.C.C., headed by former Japanese porn-star Mayuko Hino. One senses a socio-political fetishism with the work of Con-Dom, formed by Mike Dando to explore the many sides of personal faith. In a sensuous merging of body and machine, the French sound-composer Manon Anne Gillis

gives birth to her noise. Intimately demonstrated by a 1995

performance, in which she kept pulling out, from under her dress,

strands of audio tape accompanied by the sound of recorded material

being yanked over the playback heads of a tape-deck.

Many noise artists are fixated on either one sound, or one type of sound. A.M.K.

uses, as his only sound source, the montage. His montages are

flexi-discs that he cuts up and recombines and then plays on regular

turntables. Even his CD releases sound just like broken records. A.M.K.

started to cut up readymade flexi-discs in 1986. Eleven years later he

would start to record and release his own limited-edition flexi-discs

for the sole purpose of montaging them.

Zipper Spy

is an avid collector of zippers. She also loves the sound zippers make.

Amplified zippers may not be the only sound source she plays with, but

zippers are nearly always the dominant ingredient in her compositions.

When asked why she loves zippers so much, she simply replied; "I hear

zippers in everything."[citation needed]

Others base their sound on the type of audio equipment they build for themselves. Both Chop Shop and Speculum Fight are examples of this approach. Chop Shop was formed by Scott Konzelmann.

Konzelmann builds speakers. Since ’87 he’s been developing his speaker

constructions to focus the listener into linking physical sounds

through visible sources[1]. Konzelmann thinks of it as a kind of ventriloquism.[citation needed]

Speculum Fight, otherwise known as Damion Romero,

presumes to deal with tones and frequencies that are intended to be

seductive to the listener. To achieve these soundscapes, Romero uses

custom-made microphones, and antique audio test-equipment re-wired as

feedback generators.

The noise-poet blackhumour, who has been active since the mid-80’s[citation needed], uses only recordings of human voice. Some noise critics[citation needed]

have described blackhumour’s work as a hybrid of noise and literature.

However, blackhumour has stated on many occasions that he sees his

noise as an extension of literature. Godzilla, not literature, is the

inspiration for Daniel Menche‘s

recent interest in human voice. Since 1988 Menche has carefully crafted

noise from sound sources like his heart, lungs, chest, and fist.

Kimihide Kusafuka, better known as K2[citation needed],

originally came onto the scene in 1984, just to disappear from it a few

years later. He returned in 1993 after graduated as a pathologist. K2

sees no difference between the act of making noise and the act of

science. K2 says he practices a kind of alchemy through his noise. He

aims to metamorphosize himself with both the insight he gets from his

scientific experiments, and the emotional strength he gains from

performing and listening to noise. "Noise..", as K2 puts it, "can not

be refused by either ears and heads!"[citation needed]

GX Jupitter-Larsen

enjoyed listening to the scratches etched across the grooves of a

record much more than the recorded material stamped onto it. Thus the

self-titled, silent vinyl record "The Haters",

which he released in 1983, comes with instructions that informs the

holder that they must first complete the record by scratching it before

it can be listened to.

[edit] References

- ^ Chop Shop (23five.org). Retrieved on 2008–01-14.

[edit] See also

[edit] External links

Paul Hegarty: “Noise/Music: A History”

Paul Hegarty is a philosophy lecturer at University College Cork, with an interest in what he wouldn’t call the genre of noise (“music”). A book either giving a history of noise’s development, or an exegesis of its socio-philosophical implications would have been interesting. Unfortunately, this is neither.

The opening chapter sets off at a fine intellectual gallop "for Kant … for Russolo. for Cage… Attali too. As… Ardono" – this is from a single page! Elsewhere, Nietzsche, Heidegger, Bataille, Hegel et al. All appear… a little too like the first attempt at a doctorial thesis, then in later chapters citation either runs out completely or revolves around another of Hegarty’s interests – Adorno on Jazz, but not the Jazz here, (and why Jazz?). Bataille on Sade. There are inclusions – too many: Improv, Punk, The Grateful Dead, Prog Rock! and self confessed notable exclusions – and others not Reich’s pendulum music Lou Reed’s “Metal Machine”, The Gamelan, Harry Partch. The whole New Zealand phenomenon.

How Hegarty gets away with this derives from two of his arguments, first that anything can potentially be called "noise", as in his long example of Yes’s Tales of Topographic Oceans – well yes! –, but no mention then of Abba or Mantovarni. And secondly, that the avant-garde in music has often been described pejoratively in its beginnings as “noise”, or, as in the famous case of Sir Thomas Beecham, as shit – but this is beside the point. The point being "noise" applies to a particular phenomenon in music as an identifier and not a critique (Pop Art is not Pop Art because it is or was “popular”).

We know, and Hegarty certainly does, that such games can be played with definitions – this is Wittgenstein’s famous “game”. To conflate the genre of noise, the “thing” with the same word applied as an attribute or subjective opinion of any music or sound is something of what I would call an ontological mistake of the first order. Or is it a strategy because it allows Hegarty to discuss any artist he wants to.

For instance, the space given to Cage and his silences – relevant by being irrelevant to the point of being a binary opposite – he might say? When after several chapters we get to actual Japnoise, and a further chapter on Merzbow, the irrelevance of much what went before becomes obvious. But here Hegarty fails to deliver what the patient reader might want – might expect, a detailed account – it’s all apologies. «This chapter will not so much deal with the specificity of noise music from Japan».

He then goes on to a consideration of McLuchan on globalization, to raise the question: «what kind of world is in or behind world music». «World music»? I’m confused? This is a very confused history, and one which fails to pick up on the development of noise from Japan back to the USA and Europe, where it has been taken up as a definite genre, having its own festivals, labels, retail outlets both on and off-line, and even now its own proto-industry of designed and manufactured devices marketed by such as noisefx.com.

Widespread broadcasting on US University campus’s and across Europe as radio and webcasts, of dedicated websites to the promotion of noise labels such as PacRec, artists like Wiesse and The Rita.

As a history the book this is chronology flawed, as a serious study the attempt to buttress certain artists (irrelevant to the genre in many cases) by relationships to certain philosophers seems strained. The book lacks structure and appears more like a set of articles, some written in an academic style, others not.

A detailed chronology, discology would have been useful. Works are referred to where perhaps a copy of the score might have been illuminating, even some pictures would help what is aesthetically a remarkably dull book. An accompanying CD or at least pointers to MP3s on an associated site would also have helped. I think that there is a sufficient body of material, artists, events, labels, online and actual retail outlets, manufacturers, chronologies and general dissemination of what can be called noise to warrant a study which does not piggy back on to it philosophical critiques of Cage, Jazz, Prog Rock, Punk and Rap, amongst others. Unfortunately, that’s what Hegarty appears to do.

Maybe we can justify such irrelevance in this communication (of a history of noise music) as being itself yet another example of “noise”, but the genre of noise music is nothing to do with the unwarranted junk found in communication, or if it is, how is it, and why is it?

[Book by Continuum > hagshadow@hotmail.com]

Your friendly neighborhood THX 1138

xxx

snakefinger - living..> 12-Feb-2008 21:06 3.4M

the cramps - teenage..> 12-Feb-2008 21:03 4.2M

the dictators - slow..> 12-Feb-2008 21:00 4.0M

minutemen - you need..> 12-Feb-2008 20:57 3.2M

alan vega - every 1 ..> 12-Feb-2008 20:54 3.8M

the stooges - down o..> 12-Feb-2008 20:51 3.4M

dead kennedys - too ..> 12-Feb-2008 20:48 2.7M

martin rev - rocking..> 12-Feb-2008 20:46 5.1M

p.i.l. - flowers of ..> 12-Feb-2008 20:42 2.6M

the velvet undergrou..> 12-Feb-2008 20:40 3.1M

throbbing gristle - ..> 12-Feb-2008 20:37 2.3M

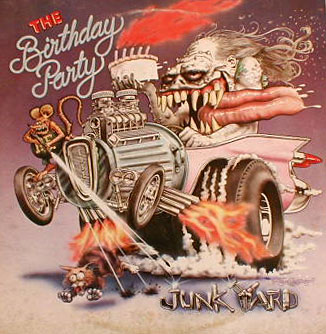

the birthday party -..> 12-Feb-2008 20:35 2.6M

the heartbreakers - ..> 12-Feb-2008 20:33 3.3M

pere ubu - untitled ..> 12-Feb-2008 20:30 3.2M

the residents - perf..> 12-Feb-2008 20:27 1.0M

flipper - i'm fighti..> 12-Feb-2008 20:27 2.5M

dead boys - ain't no..> 12-Feb-2008 20:24 3.2M

devo - secret agent ..> 12-Feb-2008 20:21 3.3M

patti smith group - ..> 12-Feb-2008 20:18 4.5M

p.i.l. - annalisa (f..> 12-Feb-2008 20:14 5.5M

keith levene - i'm l..> 12-Feb-2008 20:09 3.5M